0887—006

УДК

ББК

908

85.16

Г55

Venets. Welcome

to the Ideal

Г

Без объявл.

906(00)—17

Pr.

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

Ep.

Ascension to “Olympus”

RU

RU

LENZNIIEP ALBUM 1970

THE FUGITIVE

Lenin's Way

Komsomolets and Pravda

Venets Regained

First Secretary's

Way

The Prisoner

In The Shadow

of City in Flower

In The Search of a Lost Hat

I.

THE

FUGITIVE

April 11, 1970. Journalist Boris Merz arrives

from Moscow to pre-jubilee Ulyanovsk

Story by

Grigor Atanesian

Translated, from the Russian, by

Thomas H. Campbell

he plane arrived at Ulyanovsk Airport at eleven in the morning. Boris Merz sat in a window seat, wearing a wool suit. He was doing up his tie in case someone was there to meet him. He had not received exact instructions on this score. He had agreed at the last minute to replace Komsomol Pravda reporter Alikhanov, who had taken ill. However, the editor of Building Publishers had little idea what reporters did.

T

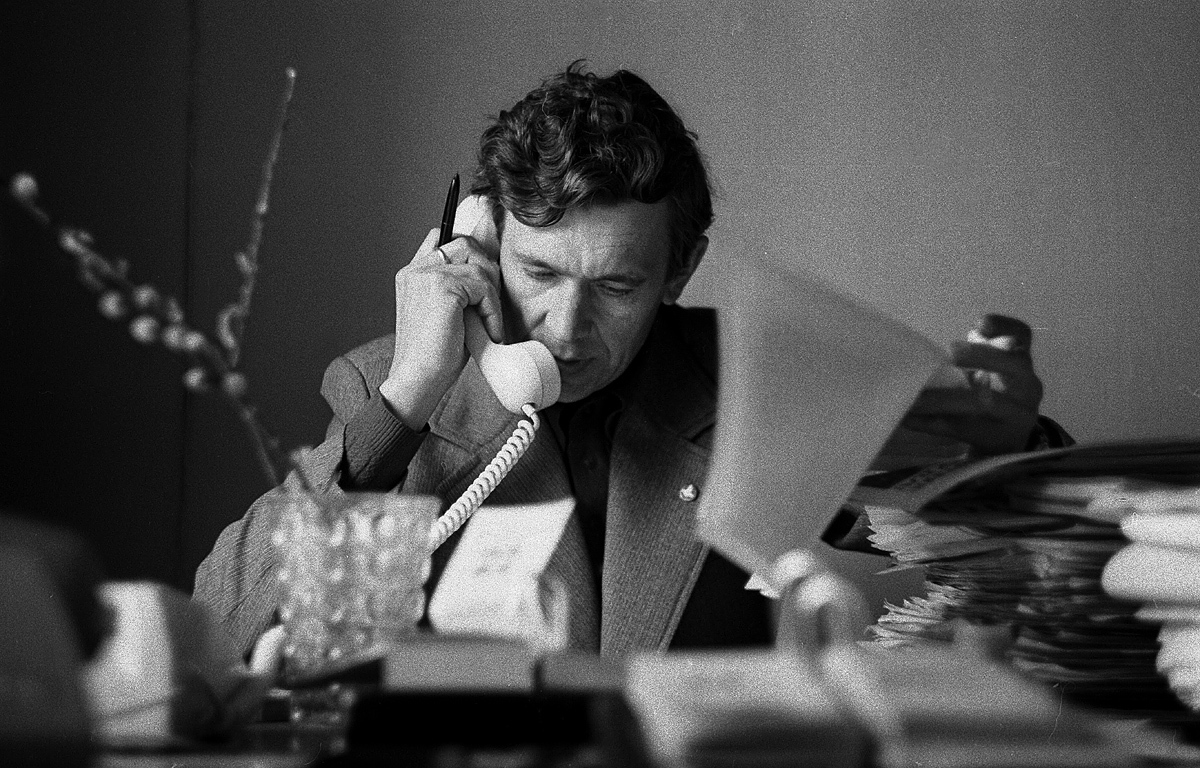

Fig. 17

Ulyanovsk television Chief News Editor Valery Alekseyevich Antipov. Photographer Boris Telnov.

Merz tied his tie, wiped his glasses, and opened a notebook. Untimely thoughts crept into his head. Alikhanov had, in fact, gone on a bender, right? Thoughts like that rattled Merz.

“I devoured Kazakov’s new story on the train. There are quite good passages here and there. ‘When we walked out into the November evening’s slate darkness…,’” he wrote in the notebook.

The airliner touched down on the concrete runway and headed for the concourse. When Merz exited the airplane and stepped onto the ramp, the concourse exploded with raucous applause. Believing for a minute the good people of Ulyanovsk were warmly greeting him, the editor smiled in confusion. Young Pioneers stood holding flowers, but they were in no hurry to hand them to Merz. When he stepped onto the tarmac, the airport again exploded in applause. He turned to the stewardess who had descended the ramp behind him.

“Who are the comrades greeting?”

“They’re rehearsing an important event. Ulyanovsk is looking forward to a very important visitor on the sixteenth, Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev.”

Merz got into a new light-green Volga, and the driver switched on the meter. The rate was ten kopecks per kilometre. Red flags and banners had been spread over the streets of Ulyanovsk, extolling the great Lenin and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, responsible for all the Soviet people’s victories. They drove through a square named for Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. The dark expanses of the Volga River were visible beyond the gigantic sculpture of the great communist leader.

What surprised Merz, however, was the abundance of buildings from the so-called private sector. The old huts along the sides of the road made a strikingly unpleasant impression on him after the new airport, which had seemingly arrived straight from the future. Merz did not want to imagine the Soviet Union still harbored corners of the dark kingdom that barely saw the light of day. Many old houses had survived on the city’s central thoroughfare, Goncharov Street. Ulyanovsk’s first large-screen cinema, Dawn, was surrounded on both sides by one-storey buildings.

The old houses and church cupolas were redolent of the old native Russian spirit. Pictures arose in Merz’s drowsy brain. He imagined a Simbirsk merchant rising, crossing himself in front of an icon mounted in an expensive frame, and bowing low to the Virgin Mary before proceeding to the kitchen, where he cuffed his schoolboy sons on the nape of the neck before savouring a roll with tea. Tightening his belt, he unhurriedly went off to open the shop.

The taxi driver interrupted the editor’s daydreams.

“Venets, comrade.”

In the hotel’s lobby, Merz wrote in his notebook.

“Huge neon letters sit atop the Crown, an enormous high-rise hotel. This has been a truly national construction project. Besides Ulyanovsk Construction and its general contractor, the team from First Trust’s Building and Construction Company No. 2, a detachment of Leningrad decorators and dozens of brigades from the Soviet Ministry of Special Works laboured at the site. The Crown is ready to welcome delegates to the International Meeting of the Labour and Trade Union Movement.”

Merz knew he was meant to have a room on the eighteenth floor, but the personnel at the Crown were not on the top of their game. Slightly embarrassed at first, he hastened to get into the role of a national newspaper reporter, and half an hour later he brandished a Komsomol Pravda ID in the face of the hotel’s deputy manager.

Meanwhile, he received a telegram. Moscow informed him the reporter should be ready for the interview.

Merz took a handkerchief from the breast pocket of his jacket and wiped the sweat from his forehead. He firmly made up his mind that the conversation should be no nonsense. He would ask point-blank questions about the international agenda. Mao was pushing for a total break in relations, and the Americans were itching to go into Vietnam. Pravda’s front page crackled with headlines like “We Won’t Allow It! This Shall Not Pass!” International relations had not calmed down in the aftermath of Paris and Prague, and now this.

But this was not why Leonid Ilyich was personally coming to unveil the Lenin Memorial?

Was he coming to affirm current policies? To check the clocks? “We Cannot Isolate Ourselves from the World!” Merz imagined headlines for the articles, which incidentally, if everything went well, could also cover him in a certain amount of glory.

The room was spacious. It wasn’t anything like the typical “mini.” It had a large window, an armchair with wooden arms, a writing desk, a magazine table, and its own telephone. And a pretty, unusual floor lamp. The bathroom was entirely done in white tile. There was a rectangular light over the mirror, an oval sink, and a shower curtain sporting a rhombus pattern, just like the pullovers now coming into fashion.

erz woke up at two in the afternoon. A beam of light fell directly on the magazine table, on which an invitation lay. Glancing at it, Merz immediately woke up. An hour ago, when he had plopped down on the bed, there had been no invitation on the table. To make certain he was not dreaming, the editor snatched the invitation from the table with one hand while with the other reaching for his glasses, which he had put on the bedside table.

M

The following text was written in red ink on white paper:

Dear B.M. Merz,

The Ulyanovsk Regional Committee, the Communist Party City Committee, and the Executive Committees of the Regional and City Councils of Workers’ Deputies invite you to the grand opening of the Lenin Memorial Complex.

The event will take place at 4:00 p.m. on April 14, 1970, on Memorial Centre Square.

Valid for entry when presented with Document No. 010727.

Merz took a long shower. After finishing his ablutions, he donned a bathrobe, opened the door, and reached for the notebook and pencil in his coat pocket. He sat down in this garb on the stool with which the bathroom was furnished and hastily jotted across the page, “The room is like paying a visit to socialism.”

The editor exited the room with the firm intention of inspecting the Lenin Memorial. He walked to the elevator and had stopped in front of it when suddenly he felt a hand on his shoulder. Turning around, Merz initially saw a very dark, well-built man, and then a familiar, smiling face with lively Asian eyes.

“Comrade Merz, are you a lone wolf? How about dining in the company of an architect?” said the swarthy man, smiling and patting him on the shoulder.

“Harold Garryevich, they tell the truth when they say you have become quite the Afghan! At first, I thought you were a trade union delegate from some socialist banana republic.”

“Well, I can imitate a delegate, too. What does a delegate do? Attends banquets and dozes during meetings?”

“He reports on the campaign against the remnants of the clerical mindset: ‘During the period in question, 120 mullahs were shot and another three thousand were impaled.’”

“That’s why, young man, I became an architect. I would have made a lousy executioner. Where is this conversation going, by the way?”

Merz and the swarthy man exited the elevator on the second floor and went into the restaurant. A waiter led to them a table next to a huge window that went down to the floor. The table was set for four. The cloth napkins flared like trumpets, and two types of crystal glasses with gilded rims stood next to the utensils.

A waitress came to the table. She was a plump young woman with her hair brushed high, wearing a white coat with short sleeves. The swarthy man immediately ordered two black coffees and turned to Merz.

“Do you see that big thing at the other end of the room? That’s the latest Italian coffee maker. It makes world-class elixirs.”

“You don’t say! And was Henry Ford invited when the coffee maker was unveiled?”

Two people had come to their table: a plump, smiling woman and a dour man with a curly forelock. They needed no introduction. Who would not know Olga Vysotskaya, an announcer at All-Union Radio? And any reporter who had come to Ulyanovsk could not fail to know Boris Lantsov, chair of the City Party Executive Committee.

The swarthy man introduced Merz, praising him in every way possible. Vysotskaya listened very carefully, without distraction, but Lantsov excused himself and hurried away. While the renowned radio announcer was talking to the waitress, Merz turned to his companion.

“You haven’t read any of my articles, have you?”

The other man merely laughed.

“You’re still young, Comrade Merz. I get the news faster than you print it, and when you are my age you have to take it easy on your eyes. Boris Dmitryevich spoke well of you to me, and I set stock by what he says.”

“Harold Garryevich, did you get an invitation to the opening of the Memorial?”

“Yes, Boris, I suppose they wouldn’t open the place without me, but what’s eating you?”

The editor hesitated for a second. Then he looked at his interlocutor.

“Listen, was it left in your room?”

“Whatever for? It was sent to the Union of Architects in Moscow last week. What’s up, Boris?”

“Oh nothing, Harold Garryevich, I was just curious.”

The swarthy man looked astonished, but Lantsov rescued Merz from the need to explain himself. Visibly agitated, he had returned to the table.

“Be ready to carry the can,” he said quietly but insistently after turning abruptly toward the swarthy man.

“Be ready to carry the can,” he said quietly but insistently after turning abruptly toward the swarthy man.

The swarthy man was taken aback.

“So we shouldn’t expect Mezentsev?”

“No. We’ll talk it over afterwards.”

Hastily quashing the awkward moment, Lantsov turned to Vysotskaya.

“Comrades, as chair of the City Party Executive Committee, my primary duty is to make sure not a single person dies of hunger during the opening of the memorial. So I suggest we urgently start eating,” he said deliberately cheerfully.

Everyone laughed except Merz. He looked at a folding door at the other end of the restaurant. Through the open door he could see a small room resembling an exhibition stand at a furniture factory more than anything else. The tiny area was occupied by a table, a chair and, to the chair’s right, a stand. Next to the stand was a sofa, half of which was blocked by a floor lamp on a pedestal. A young woman of eastern appearance sat on the sofa, holding a telephone to her ear. She wore high boots and a red buttoned dress.

The young woman leaned her head against the wall. She was talking on the phone, but her gaze was fixed on Merz. Her movements were absolutely indecipherable, and it had to be supposed she was speaking the language of an ethnic minority. Finishing the conversation, she put down the receiver and made her way out of the restaurant. Her red dress and swaying gait seemed out of place to Merz, superfluous and inappropriate amid the correct rhythm of the tables, the pastel colours of the armchairs, the large windows, the white napkins on white plates, and the ceiling’s geometric pattern. As soon as he thought this, a curious thing happened. A heavy man in an astrakhan hat who was entering the restaurant stepped aside to let the young woman pass, and he knocked over a tall ashtray on a pedestal. The ash scattered on the carpet, and the man rushed to pick up the ashtray. The young woman, however, did not turn around. She left the restaurant.

The editor took little part in the conversation after this incident. He gazed absentmindedly at the triangular sections of glass-covered mahogany on the ceiling. Ordinary light bulbs had been installed under the glass. The editor took out his notebook and wrote.

“The restaurant’s ceiling resembles an artificial sky. It differs from the starry frescoes in Gothic cathedrals in the sense that it does not pretend to be the product of divine intervention. On the contrary, it cries out to the observer that it was made according to the calculations of modern engineering, and it exposes its own blueprints. This is also an important sign of our time. Our professions and disciplines can longer pretend to be guild or family secrets. The more accessible information there is, the more quickly a sector develops, and the more food for thought there is for professionals in related fields. So, in the end, overall progress is established.”

In the evening, after visiting the Lenin Memorial, Merz worked in his room on the article while his hand was still fresh. He was worried. He did not know why, and so he left the luminescent lamps installed behind the blinds turned on. Their soft lunar light soothed him.

The editor washed up, went back to the desk, and shuffled the papers. In keeping with a habit acquired during his student years in the dormitory, he placed them in an even pile so that when he awoke, he could work at a neat and tidy desk in the hour before breakfast.

The invitation from the Regional Committee fell from the pile of papers right-side down. The name Lenin was stretched across a red sky, and the foreground was occupied by a schematic rendering of the memorial building. The figures “1870•1970” had been printed on the bottom of the invitation. And to the right of the second date, someone had written, “Midnight, Youth Café” in a childish, irregular hand.

he last flight left Ulyanovsk Airport at 11:30 p.m. The lobby was terribly stuffy, so Merz ran outside now and then to smoke. He could think clearly in the fresh air and with a cigarette between his teeth, but he was chilled to the bone and shivering. A cold wind had blown into Ulyanovsk the day of the opening and had not stopped blowing until the day of his departure.

T

Merz tried to think how he would go to Komsomol Pravda the next day to explain why he had submitted an architectural essay to them instead of an interview with Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev or, at least, with Skochilov, First Secretary of the Ulyanovsk Regional Party Committee. Or rather, why he had not brought them anything. He had come up with the idea of doing an architectural essay in the taxi on the way to the airport and was planning to write it over the next two days, but he had no intention of explaining this in the editorial office. He intended to walk in looking confident, convince the editors his approach was original and the topic was fresh, and then beat a quick retreat, claiming he had caught cold, and then finish off the article in two days. He had already written the first paragraph.

“Even before the arrival of the honoured guests, before the scissors kissed the red ribbon, and the city’s labourers had cordially greeted Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, it was obvious the people of Ulyanovsk had passed their judgement. Built as part of the memorial, the wide esplanade has become a favourite spot for the city’s inhabitants to stroll in the early days of April, when the Volga had completely freed itself from its icy shackles. As they walk around the giant complex, many people stop next to the huge granite-and-marble wall on the Memorial’s façade, where the following phrase has been cast in bronze: ‘This building was erected to commemorate the centenary of Vladimir Lenin’s birth.’ The people of Ulyanov walk over the multi-coloured granite slabs of the inner courtyard, arriving at the sacred cradle where the great communist was born a hundred years ago. Ilyich’s house has been rejuvenated. It has been carefully restored to the way it looked on April 22, 1870.”

The article was not the only thing on his mind, however. He was hampered from thinking rationally about important matters by the sense of utter indifference that had engulfed him at the Crown.

A few hours earlier, he had been sitting in the hotel’s deserted lobby in a low-slung armchair with his back to the exit and putting out one cigarette after another in a cuplike, shoulder-high ashtray on a stand.

“It’s pretty, but it’s been placed in an awkward spot. The next thing you know you’ll be flicking ash on the scruff of your neck,” was the thought that raced through Merz’s head before swerving off the road and crashing into a ditch.

“What was I thinking about.”

He crushed a cigarette in the ashtray with one hand while reaching for the pack on the table with his other hand. He lit a cigarette, closed his eyes, and thought about nothing.

Opening his eyes a few seconds later, the editor saw the same empty lobby of the Crown, the clock on the wall with a round dial nailed to a metal frame resembling a helm, and the staircase along the far wall, whose windows reached the floor. The clock showed a few minutes after ten. Merz had to call a taxi, but instead of the manager’s desk his thoughts drove him toward the staircase, where rows of square lights rose toward the ceiling diagonally.

His thoughts raced through the three sections of the restaurant on the second floor. While Merz waved away the cigarette smoke, they were already rising above the restaurant, the snack shop, the souvenir store, the three hundred single and double rooms, towards the two-room and three-room suites, outpacing the fifteen noiseless elevators and ascending to the Crown’s apex. A reel of film containing a treacherous, bourgeois, and confused movie had begun to unwind, a devilishly beautiful movie, a senseless, unnecessary movie with no message, with no call to arms, except drunkenness and idleness.

“I dreamed the whole thing, I dreamed the whole thing,” Merz repeated, knowing all too well the nature of what had happened was purely materialistic.

And if right at that moment Old Man Hottabych had approached him instead of a waiter and offered to undo what had been done, to inscribe a rhombus in a circle, to take everything back, then the well-bred even timid editor of the country’s central scientific and technical publishing house would have grabbed the old man by his grey beard and bashed his head against the streaked stone column in the hotel’s lobby.

n the evening of April 11, Merz had looked long and hard at the invitation from the Regional Party Committee. For some reason, he flipped it over and back, as if hoping the message in pencil would vanish. Finally, he hastily placed the invitation on the desk and sat down on the chair awkwardly, sideways. He glanced at his Rocket wristwatch, produced at the Petrodvorets Watch Factory. It was half past eleven and so the hope he had already missed the secret rendezvous was in vain.

O

Merz blinked. When he was nervous, he blinked.

The editor of Building Publishers did not count courage as his principal virtue, and he did not like thinking about going into a bar in the middle of the night to meet someone based on an anonymous invitation delivered to his room in an indecent manner. Merz frowned, undressed, and lay down on the bed, leaving the luminescent lights behind the blinds switched on. He could not sleep. At a quarter to twelve, Merz finally persuaded himself he must put an immediate end to this stupid joke, whoever the joker was.

The editor entered the cube-shaped building of the Youth Café slowly and warily, like a Soviet tanker entering the Suez Canal. The sign “No room” hung on the second door past the cloakroom. Merz paused and pushed the door.

An employee stopped him at the entrance.

“Bar’s closed, comrade. Been closed an hour.”

The editor was about to turn around and go, but a man in glasses waved to him from the other end of the establishment. The employee stepped aside.

Merz went to the other side of the room, where he was met by a ubiquitous Moscow acquaintance, the photographer Abdeykin.

“Boris, as always, wearing a tie. What you doing in a watering hole so late at night?”

A sweaty bottle of beer stood on the photographer’s table next to a brand-new Zenith 6 camera with a long lens.

Merz hesitated. If Abdeykin was also here now, they could be part of the same trick on him. But if not, it would be better not to tell him anything so as not to look like a fool.

“How embarrassing! This is funny. What brought you here?”

“I’m on assignment. And you? Weren’t you the guy who said the North was your destiny? Exploring distant frontiers? Don’t tell me the Arctic Ocean has come to Ulyanovsk?”

“The fees dried up in the North. Ulyanovsk is now the hot spot. Here, by the way, is my latest acquisition, a Ruby 1C with variable focal length.”

The photographer pointed to his lens. The editor nodded and sat down at another table. When a dandyish waiter came to his table, he ordered a glass of the local draft beer.

“Two-year courses at Intourist and an ID from the Ministry of Commerce,” Merz thought with contempt.

When the glass was set down on his table, the editor flinched. He had forgotten the time. The second hand on his Rocket wristwatch raced towards twelve o’clock, overtaking the other two hands. It was midnight. Merz looked at the entrance. He recognized the red dress first, and the young woman’s eastern features immediately after. She smiled at him, passed through the entryway, and sat down across from him.

“Hello,” she said, looking straight into his eyes.

The hard to pronounce combination of three consonants in the first syllable of the greeting immediately revealed a non-native Russian speaker’s accent.

“Hello. Boris Merz.”

“I know. Reporter for Komsomol Pravda, eighteenth floor, room thirteen, as it were.”

Merz blinked. It was either the superfluous “as it were” (the editor would have crossed it out if this had been an article) or how much the young woman in red knew about him.

“And I’m Nana.”

“Comrade Nana, have you been following me? Why?”

The young woman laughed loudly, like a young person. Merz examined her face. She was beautiful, but her beauty was definitely eastern: a swarthy face, ominous black hair, brilliantly velvet black eyebrows. Her eyelids were almost half lowered, and only when she laughed would her eyes open and the corners of her mouth form the correct smile of a Cheshire cat, exposing the little white carnivorous fangs under her puffy lips. He guessed she was a quite young woman, maybe nineteen, twenty-one at most, which generally explained her erratic behaviour.

“Why would anyone need to follow you if this very morning you told the whole lobby your name, position, newspaper, and what floor you’d be staying on?”

“Okay, but what business do I have with you?”

“Listen, Comrade Merz, I’m bored, and everyone round here is a fool. And if you push it just a bit more, I’ll be bored with you, too, and decide you’re like all the rest.”

“A fool?”

“I can’t rule out that possibility. So what are you drinking, Comrade Merz?”

Merz shrugged. The young woman got up and went to the bar. She came back a minute later with a bottle of beer.

“Have you seen the Memorial already, Comrade Merz?”

“Yes, of course, it made a very strong impression.”

“No kidding. First, they ran a bulldozer over the city, and then they plopped down a concrete barn and are so happy they could die. A strong impression, indeed.”

“I would say that sounds like the judgement of a very stupid person if you weren’t so young.”

“And what is the judgement of the venerable reporter?”

“We should build more such architecture! However many times you nail our Soviet coat of arms to a classical portico, it will still be a reminder of the past. We don’t have time for that! We need to build new things. Old streets lined with old trees and nineteenth-century tenement buildings on both sides of the streets produce a consumerist reflex and useless thoughts.”

At twenty to one, when the waiter brought Mertz and his companion the bill and told them the Youth Café really was closing, an outside observer might have imagined they were on the verge of fighting. They were, indeed, arguing tooth and nail. The young woman had adopted an aesthetically reactionary stance and defended old Russian architecture, for which Merz felt no sympathy whatsoever. He could not understand how a decent Soviet person could find value in something so deeply stained by its profound links with clericalism and the Black Hundreds.

Merz thought the student was blatantly mocking both the team who had designed the Memorial and the latest architectural trends he liked so much. He already despised her deeply, and the more she spoke, the more he considered her not only stupid but also as someone who was saying outright harmful things. Several times, he caught himself thinking he was no longer listening to her answers, but only watching her lips move.

Merz wanted to pay for the two of them, but the young woman would not stand for it. She took the bill back and counted out her share. Then she put her wallet into a shiny bag and pulled a cigarette from it. Merz had the urge to smoke. Catching his gaze, she pointed at the pack.

“Have a smoke, Comrade Merz.”

Merz had no desire to be indebted to this brazen girl, even over such a trifling matter.

“Thanks. I’ll buy myself a pack if I want to.”

She did not laugh, but the corners of her lips lifted.

“You’ll have to wait until morning, unless there is a special store for national newspaper correspondents, where cigarettes, French perfume, and chocolate are sold around the clock.”

Merz nodded, took a cigarette, and reached for the matches, but she had already lighted one and looked at the flame. Her gaze slid down the tip of her nose, under which the match burned in her hands, and then somewhere right between Merz’s eyes. She slowly moved the match towards his cigarette, holding it long enough for the flame to burn her fingertips. Merz noticed the spark in her eyes, and then what long, thin fingers she had.

n the morning, Merz bitterly regretted he had not set the alarm clock. For years now, he had got up before seven, but that day he had woken up only after ten. The first three hours of the day, from sunrise to nine, were the best time to work, the time when he dealt resolutely with the most hopeless manuscripts. Today, he had got up unforgivably late, and all because of beer and a trivial conversation he should have never had.

I

After breakfast, Merz went to work at the offices of Ulyanovsk Pravda, but the front door was locked. Merz rang the doorbell every fifteen minutes, distracting himself by examining the Ionic half-columns by the main entrance, the rustication on the first floor, and the pilasters, before ringing the bell again. Finally convinced that no one was coming downstairs to open the door for him, he walked to the nearest payphone and dialled the secretary whose responsibility it was to provide him with a workplace.

“Comrade Merz, you’ve woken me up. We’re closed today, come tomorrow,” said a sleepy woman’s voice.

The editor went away, but life in Moscow breaks one of the habit of just strolling around with nothing to do. And so he thought of something to do — buy pencils and notebooks in the brand-new Central Universal Department Store. In cupboards at the centre of the store, porcelain plates bearing the likeness of Vladimir Lenin on a red background, crystal wine glasses, plates, and ashtrays were displayed, while under the geometric pattern of square lights, descending from the ceiling on thin cords, jutted the tiny legs of brand-new showcases. They were manned by female workers in short-sleeved shirts who competed in pairs to show customers the Central Universal Department Store’s assortment of goods. Merz bought two notebooks, pencils, and a pack of cigarettes.

Merz spent the rest of the day working in his room. The young woman in the red dress kept twirling in his head the whole day, finally occupying all his thoughts. The editor decided that perhaps she was not spoiled at all, and he regretted getting angry yesterday. He asked himself, even if she had been goading him on purpose, would it have not been more instructive to reply calmly, like an adult, like a man?

The doorbell rang after nine o’clock. The swarthy architect stood at the door.

“You playing the hermit, Boris? Will you have supper with us? Be downstairs in five minutes. I’ve reserved a table, and I’m not taking no for an answer.”

Merz dressed and went downstairs. The swarthy architect recounted vividly how Skochilov, First Secretary of the Ulyanovsk Regional Party Committee, had had a falling-out with Lev Mezentsev, leader of the design team and, in fact, the designer of the Lenin Memorial. Ultimately, Mezentsev had not been invited to the opening of the Memorial, and the swarthy architect had been delegated by the architects to accompany Brezhnev and Skochilov to all the official events on their behalf.

Merz was lost in his own thoughts. He listened inattentively until finally he was staring off into space. He was roused from oblivion when the “Afghan” uttered a familiar name.

“Nanochka, we’re over here!”

That evening, the young woman was wearing a pomegranate-coloured dress and shoes the same colour with gold clasps.

“Boris, meet Comrade Nana, a big boss and my favourite student.”

“The biggest boss. Harold Garryevich, Comrade Merz and I have already met.”

“That’s young people for you! I won’t even ask under what circumstances.”

“Under rather peculiar circumstances, Harold Garryevich. What is Comrade Nana in charge of?”

“I helped the Memorial design team a bit when it came to restorations.”

“She was head of the restoration department. To give you a notion of this person’s scope, Boris, you should know that at the age of thirty-one she commanded a team of twelve men.”

Merz blinked. He realized that yesterday he had lectured a woman two years older than him, and a professional architect to boot, as if she were a schoolgirl.

Lantsov, chair of the City Party Executive Committee, came to their table. He apologized and led Harold Garryevich away to talk with him. The young woman in the pomegranate dress quickly looked away, as if she had made up her mind about something, and turned to Merz.

“I’m going to run away from here, and there’s still a chance we can do it together. If you want to.”

Merz blinked again.

“But what about…?”

“Harold? He is only too happy to dine without witnesses. He’ll order himself two hundred grams of vodka. You shouldn’t worry about him.”

The taxi stopped outside a restaurant in a two-storey mansion on Goncharov Street, opposite the Central Universal Department Store. The waiter took them to a table near the stage. The semi-circular niche accommodated a black piano and a scrawny pianist, a couple of brawny trumpeters, an accordionist, a guitarist, a percussionist, and a female singer whose hair was pulled back. They were playing “Tenderness.”

The tables were situated amidst palms from an altogether different era, and sweaty bottles of beer stood on the starched tablecloths.

“Comrade Merz, please ask them to play another song when this one ends.”

Merz walked in front of the stage, approached the accordionist, whispered something to him, and slipped him five roubles.

“Tell me what you write about, Comrade Merz.”

“About architecture, mostly.”

One of the trumpeters started playing. The pianist picked up the tune, the percussionist joined in, and the vocalist began to sing.

You have such eyes,

As if there were two pupils in each,

Like in the newest, newest cars.

Merz blinked. Either because he remembered quite clearly that in Kristalinskaya’s original song, the line went, “Like in the newest cars,” without that second, provincial sounding “newest,” or because the vocalist for some reason was singing operatically, enthusiastically, whereas the whole point of this pointless song was the recitative and repetition.

You have double eyes,

They’d be enough for two guys.

“And what do you find interesting about Ulyanovsk’s architecture?”

“Well, today I went to the offices of Ulyanovsk Pravda to work and while I was waiting in vain at the locked door, I took in the merchant’s mansion in which the offices are housed. You would have liked it.”

“The Zelenkovaya House. One of the most interesting buildings left in the city.”

Merz did not listen so much as he followed the movements of her lips.

Your eyes, you see,

Are like the map’s two hemispheres.

The menu was brought to them.

The gifts of the oceans—fish and other seafood—are very nutritious and tasty.

Our restaurant gives you the chance to taste different dishes and hors d’oeuvres made from this produce.

Name of dish / Price

“Would you like sturgeon broth with mushroom dumplings, Comrade Merz? Or, maybe, the Surprise Salad?”

“I’m not big on fish.”

“Neither am I. Should we drink?”

The conversation once again turned to architecture, and once again Merz could not help getting angry. But he tried to speak with restraint, bearing in mind he was speaking with an experienced architect. How marvellously those lips moved! But how could she be thirty? Now it seemed to him that she was sixteen, not a day older.

At five minutes to eleven, the waiter made the rounds of the tables to tell everyone the restaurant was closing. He got a rouble from each table and backed off. Merz and the young woman had finished off a bottle of white wine. The editor noticed that in the evening she was intensely animated, as if her heartbeat were speeding up.

A man in a black jacket, who looked like a factory worker who had made his way up in the world, danced with the restaurant’s manager, a plump lady in white with curled hair. Nana ordered another bottle.

An hour later, the waiter came with the bill, and Merz, no longer doubting anything, paid the bill, slipped two roubles into the man’s pocket, gave him another twenty roubles, and nodded toward the band.

Half an hour later, the lights had been turned off in the entire restaurant except for the stage. The vocalist sang “Girl” by The Beatles in Russian translation, performing it as Obodzinsky had, straining her voice when she sang, “Ah, girl.”

“Boris, ask them to play the song about eyes again.”

They got up and danced. When they were dancing, Nana hugged him in a completely different way than the girls he knew in Moscow did—not flaccidly, but gently. She was not afraid of cuddling up to him quite closely.

Merz looked at her lips and thought only of them. The singer sang the last lines of the song, only the closing chords remained. Merz pulled Nana towards him and kissed her. Then he kissed her again, and then again, for a long time.

The lights went up, Nana pulled herself away from Merz, and left the restaurant. He went to their table, retrieved his jacket, and hurried after her. A taxi was already waiting outside. Merz got into the car next to Nana. She took his hand.

“To the Crown,” said Merz in a voice that was not his own.

he next morning, Merz searched for her all over the Crown. He asked about her in both lobbies, for Soviet guests and foreign guests, talked with interpreters waiting for foreigners, and went through all three rooms of the restaurant, the café, and the snack shop. In the Birch hard-currency store, the shop clerk recalled that a young woman matching Merz’s description had purchased seventy roubles’ worth of souvenirs the other day. He stopped by the art salon and a women’s hairdressing salon, for some reason located right in the hotel. Desperate, he went down to the restaurant. He saw his swarthy friend at a table and went over to him.

T

“Harold Garryevich, you haven’t seen Nana by any chance, in connection with work, say?”

“Sit down, Boris. What has happened? If I’m not mistaken, Nana flew to Moscow this morning. From there she was going to Batumi with her parents.”

“And what’s waiting for here there? Her grandmother?” Merz asked confusedly.

“She’s having her wedding there, Boris.”

“I see.”

“That’s right, Boris, and it’s no fun for me, either. It means she’ll have kids and will be lost to our business for another few years. It’s a shame, she’s a first-class professional. You should have seen the way she came down on me like a house of bricks when she found out we had decided to demolish the governor’s house. According to the original plan, we were supposed to evict all the offices that had dug in there, restore the place, and turn it into a local history museum.”

Merz blinked.

Read Next: Part 2. Lenin's Way 28.I.2019

„VENETS“. WELCOME TO THE IDEAL

Editor K. Gluschenko. Translators T. Campbell, M. Shipley, K. Sutton. Proofreading M. Gordis (english), T. Leontyeva (russian).

Graphic design K. Gluschenko. Author of “The Fugitive” G. Atanesyan.

Typeset 26/IV 2018. Signed for publication 1/VI 2018. Typefaces: Steinbeck (R. Gornitskiy), Quant Antiqua and Journal Sans (Paratype). Order № 157.

This publication is produced by V–A–C Foundation as a part of the artwork “Venets” by Kirill Gluschenko for the project “space. force. construction”

(V–A–C Foundation, Palazzo delle Zattere, Venice, 13 May — 25 August, 2017). Curated by Matthew Witkovsky and Katerina Chuchalina. www.v-a-c.ru. Moscow, Gogolevskiy Blvd., 11.

Published by Gluschenkoizdat

Germany 04105 Leipzig, Waldstrasse 14

Web edition designed in Verstka

www.verstka.io

Please take a look at another project by our publishing house

„1962. NIKOLAY KOZAKOV DIARIES“

1962, the Soviet Union. On the eve of the inevitable onset of communism, the truck driver from the Gorkiy Region, Nikolay Kozakov, plundered the collective farm property, went to the construction of a gas pipeline to Kazakhstan and was treated for stammering with hypnosis in Kharkov. For the ostentatious masculinity — hunting, riding a motorcycle and constant drunkenness — the secret life of a man with a developed taste, a subtle observer, a connoisseur of ancient mythology, hides. He writes poetry, takes pictures, pities himself and falls in love too often.

Radioplay is read by former anchor of Central Television of Soviet Union

Yuriy KOVELENOV

Gluschenkoizdat

leipzig•2018